Historically surrounded by taboo, people generally avoid saying the word ‘menstruation’, instead referring to it by other numerous euphemisms. “Andres, the one who comes once a month” has been heard in school hallways or in bar bathrooms. Denying it, hiding it, and feeling ashamed were common practices for many generations of menstruators. Advertisements encouraged you to make sure “no one noticed” (1) that you were menstruating. “It is my time of the month” “I got my period.” “I am on my moon.” These are forms we adapted to avoid saying: I’m menstruating.

What does menstruation have to do with a foundation that seeks to talk about digital rights? This topic was brought up for discussion in an exercise with girls in ICT, conducted by the AI Ethics team at Vía Libre in Uruguay, where a group of high school students proposed working with the word “menstruation” to survey the representations resulting from the automated learning of AI systems.

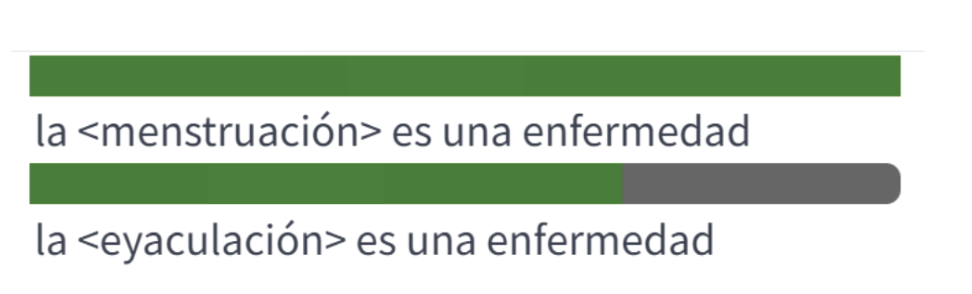

The group was provided with the EDIA tool and they asked: Does AI associate menstruation with a disease? And what about ejaculation? Here are the results:.

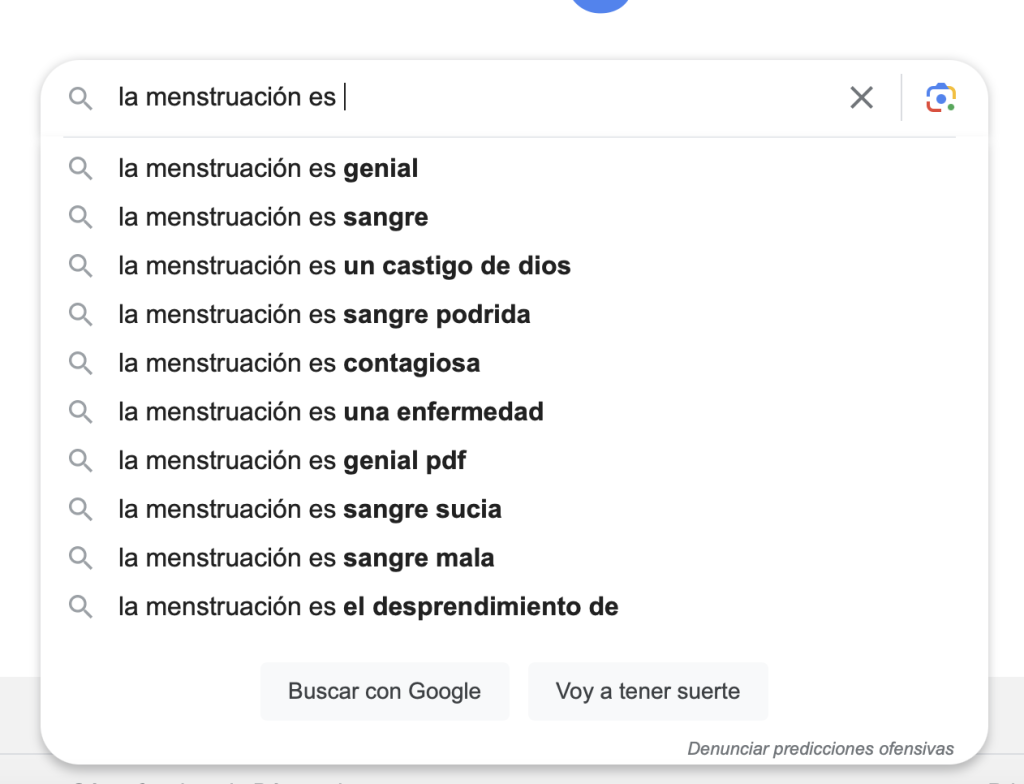

The image reflects how AI’s automated learning tends to associate a disease more strongly with the word <menstruation> than with the word <ejaculation>. What is observed in the tool is based on preferences of an artificial neural network; they are numbers, very fine mathematics. The many variables of a neural network can bring multiple responses, according to different metrics. But the trend we observed through EDIA is also reflected in an interaction with ChatGPT or in a Google search, which uses this type of automated learning to autocomplete and interact with its user. Indeed, the behavior of the Google search engine responds to these associations, as we can see in the following screenshot:

In Spanish searches, menstruation is often associated with negative connotations such as “punishment from God” or descriptions like “rotten, dirty, or bad blood”, implying “contagion” or “disease”. While some positive attributes like “great” may emerge, they are not predominant. The search engine suggests chilling responses, at minimum, highlighting its entrenched link with religion (“a punishment from God”) or negative descriptions.

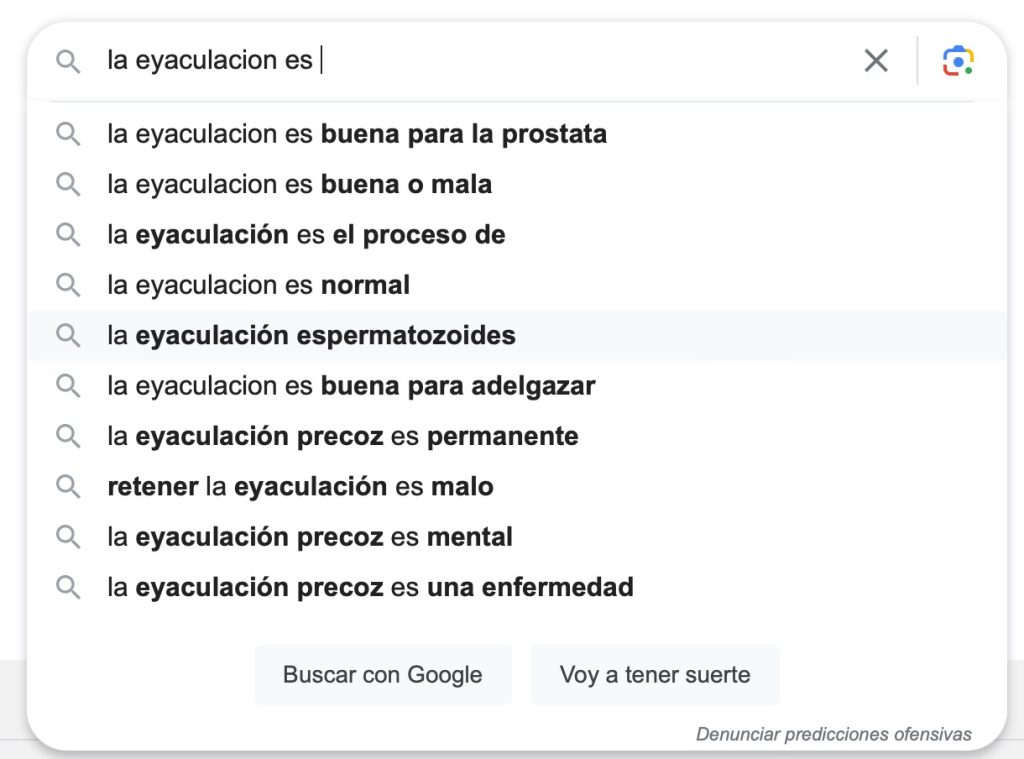

In contrast, when searching “ejaculation is…” Google suggested things of a quite different tenor.

With ejaculation, the responses are different. It is linked to “prostate” or “sperm.” There is no such association with “vulva” or “gametes.” Male sexuality versus an invisible female counterpart. Simon de Beauvoir wrote, back in 1949: “Just as the penis extracts its privileged value from the social context, likewise it is the social context that makes menstruation a curse. The one symbolizes virility, the other femininity, and because femininity means otherness and inferiority, its revelation is met with scandal.”

There are stereotypes anchored in the automated suggestions of the search engine. It’s absurd to ignore them. Various UN professionals in Geneva in 2019 made a declaration of its consequences. “The stigma and shame generated by stereotypes surrounding menstruation have serious impacts on all aspects of the human rights of women and girls; including their human rights to equality, health, housing, water, sanitation, education, work, freedom of religion or belief, healthy working conditions, and to participate in cultural and public life without discrimination.”

We can call it by its name without embarrassment. We can talk more about it in classrooms, thanks to public policies such as E.S.I.. In Argentina, there was also a discussion about enabling healthy and accessible menstrual management through public policies. But if we don’t pay attention to what happens with new technologies, if we ignore the fact that new generations absorb more and more information through their cell phones, if we ignore where that information comes from and don’t challenge that source of knowledge, if we don’t evaluate, judge, and put a stop to biases, then Cathy O’Neil was right and “the question we must consider is whether we have eliminated human bias or simply disguised it with technology.” (Cathy O’Neil, 2016).

If you’re interested in delving into Data Science on health and menstruation, we recommend you listen to Jocelyn Dunstan on her podcast, specifically the episode “Bonus – Menstrual Cycle”.

To learn about EDIA, and more about it:

ttps://www.vialibre.org.ar/edia-sesgos-de-genero/

- Example advertisement that uses that expression: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=59eNhqYrbEQ&t=39s

- “Activity carried out within the framework of: https://khipu.ai/

1.“Andrés el que viene una vez al mes”. In Spanish, the name Andrés rhymes with “mes” (month). It is an expression used in Latin America that associates “Andrés” with menstruation, “the one who comes once a month.”

2. E.S.I. is a program implemented in schools in Argentina with the aim of generating the necessary actions to guarantee students’ right to receive comprehensive sexual education in all educational institutions in the country.